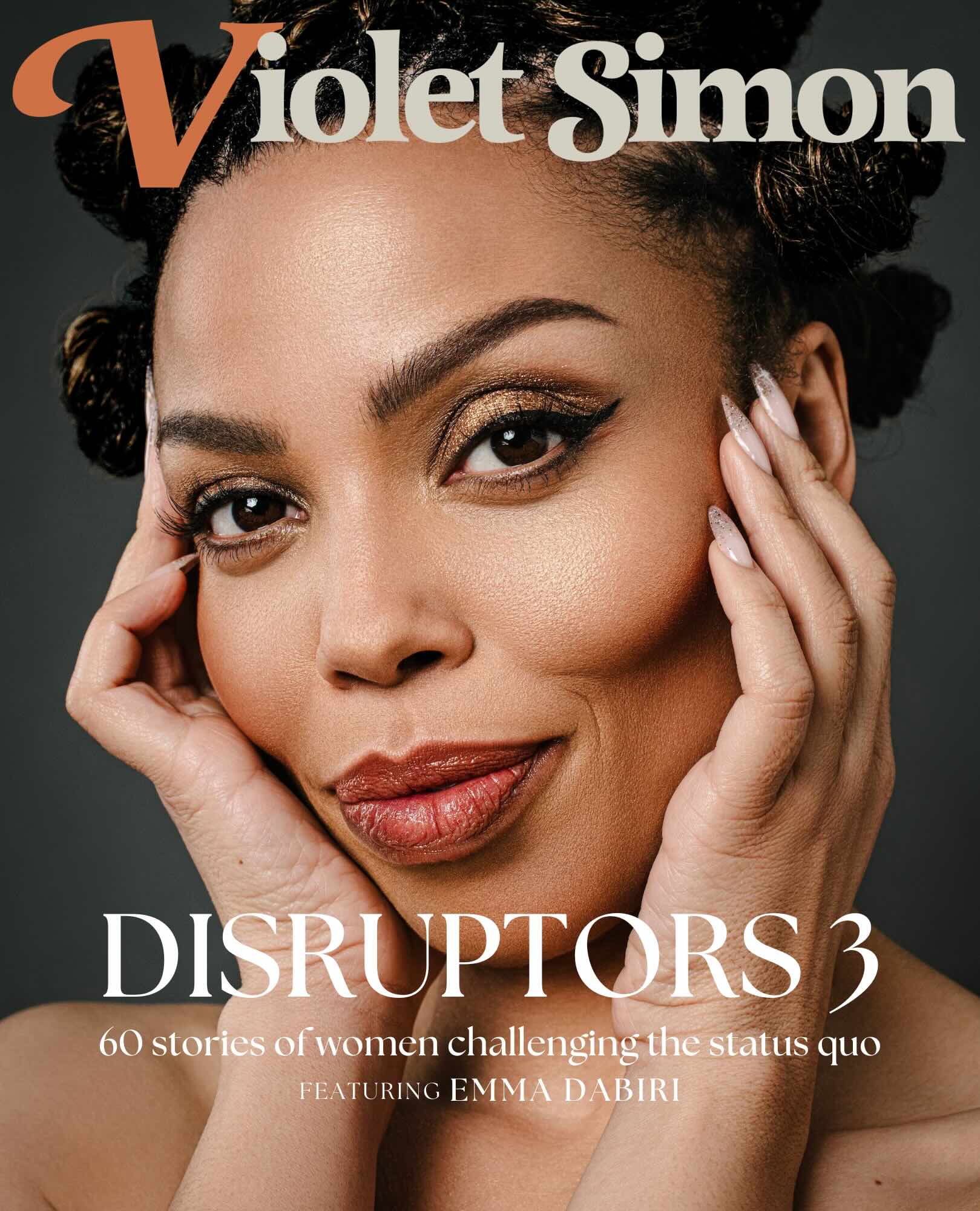

Emma Dabiri is an Irish-Nigerian author, academic and broadcaster She spent over a decade as a teaching fellow in the African department at SOAS. She is a final year Visual Sociology PhD researcher at Goldsmiths, and author of the Sunday Times bestseller What White People Can Do Next, Don't Touch My Hair and Disobedient Bodies . In 2023 she was appointed as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

She has presented several television and radio programmes including BBC Radio 4's critically-acclaimed documentaries 'Journeys into Afro-futurism' and 'Britain's Lost Masterpieces' and the Cannes Silver Lion award winning Hair Power for Channel 4. She is a columnist at The Guardian and Contributing Editor at Elle.

What is your background and what was growing up like for you? What were some of the main challenges you faced and milestones you achieved growing up? How did those experiences influence the person you are today and the profession or vocation you do today?

My mother has two white Irish parents, but she was born and raised in Trinidad, and my father is Yoruba, from Nigeria. I had an unusual childhood, in that I grew up in Ireland at a time when there were virtually no black people there and it was a 99.9% white country, very homogenous, and at that time, still extremely socially conservative. There was a lot of racism. It was very isolating and it was tough. An avid reader from a young age, I turned to books to try and make sense of my experiences and started reading black history as a child. Funnily enough, while it was my isolation growing up in Ireland that in many ways set me in the direction of my studies - I moved to the UK after school to study history and African Studies at SOAS - it was also the fiercely anti-imperialist tradition that runs through so much of Irish culture that shaped me too. As I got older, and read more widely, as Ireland changed and I started to be able to rehabilitate my relationship with it, I started to see more and more the parallels between Black and Irish radical traditions and became increasingly drawn to politics of coalition. I believe that international solidarity against oppression and exploitation is the only way we might possibly overcome all of the injustices people face globally today.

Being a disruptor means challenging the status quo and going against the grain in your sphere of life. What makes you a disruptor? What was the catalyst that prompted you to start challenging the status quo?

From a young age, I saw there was a gap between what was "official" and what was 'true" and I often had a visceral reaction to injustice and hypocrisy. I saw the way the powerful controlled narratives, but power and corruption often go hand in hand, so often what we are told is the 'right' way or the 'just' way is just the way that serves the best interests of the ruling classes and is often morally bankrupt. I think it is an ability to recognise this and a willingness to challenge hegemonic thinking that makes one a disruptor.

How do you stay resilient and determined in the face of resistance or setbacks and stay motivated?

I have a strong and singular sense of purpose. I look at the unimaginable harsh and cruel conditions people before me not only survived but organised effective models of resistance against and crafted beautiful cultural resources within the face of, and that inspires me.

A disruptor leaves a mark, a legacy. What legacy do you hope to leave?

I hope I can change the way that people think and that more people can see that more just and liberatory ways of living are not only possible but necessary.

How can we be authentic and respectful to ourselves, our bodies and each other?

I honestly believe that when we are harsh and judgmental about other women's appearances we are usually - even if not consciously- harsh and judgmental in the way we view or think about ourselves. When we cultivate more genuine kindness and generosity towards ourselves this in turn reflects outwards.

What experiences shaped and influenced your experience and views on beauty?

Growing up in a patriarchal society where women were subject to oppressive beauty standards which were triplefold for me as a black woman where the standards were so determined by whiteness, but then also when I travelled, I saw how differently I was perceived across different cultural contexts and how beauty standards - while often consistently oppressive to varying degrees - were contingent and contextual in regards to who was included and who was excluded.

The third issue of Disruptors is now available to order.

Member discussion